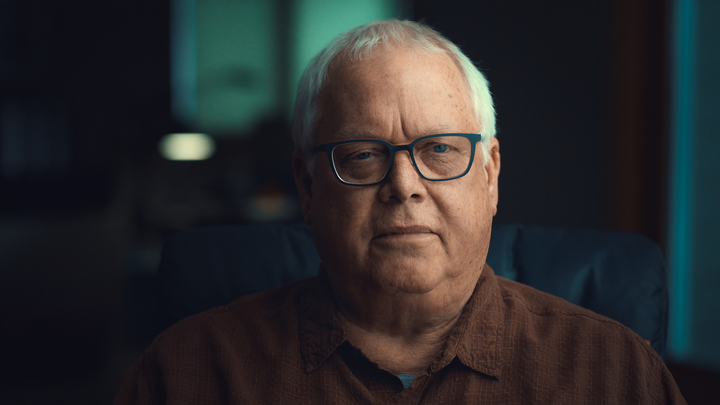

As a graduate of the second-ever cohort of the Law-Psychology program at the University of Nebraska, David Suggs, ’79, never pictured himself at the center of one of the most high-profile murder cases in the nation. Nearly 45 years after the death of John Lennon, he details his involvement in the case that followed.

“People of my generation always remember exactly where they were when they learned that John F. Kennedy was shot, when Bobby was shot, when Martin Luther King was shot, and when John Lennon was shot,” he said. “This was on that sort of level, and the publicity was just absolutely ferocious.”

Suggs had been watching Monday Night Football with his wife when he heard the news. The defendant, Mark David Chapman, had been taken into custody without a struggle.

The lawyer initially assigned to his defense had resigned over death threats, and attorney Jonathan Marks had taken over the case. Over a lunch meeting, Marks asked Suggs if he would like to help with the jury selection process. At the time, Suggs worked at Donovan, Leisure, Newton & Irvine in New York, and the offer piqued his interest.

“It was an opportunity to have a front row seat on probably what was the biggest criminal trial going on at the time,” he said. “Personally, one of the draws for me to work on that case was that I wanted to know what happened. Why did he kill Lennon?”

Having studied under Professor Bruce Sales, the inaugural director of the Law-Psychology program, Suggs had developed a reputation as an expert in jury selection. He had researched the relationship between nonverbal and paralinguistic cues and was tapped to evaluate prospective jurors in court soon after. His input was sought out time and time again.

As an undergraduate, Suggs worked on trials related to the Wounded Knee occupation by members of the American Indian Movement. He went on to survey jurors in Federal Court in Nebraska and Iowa, as well as in a murder case arising out of the Attica Prison Riot in New York. He enjoyed the cutting-edge work and accepted a position in the Law-Psychology program. This decision was a pivot from his original plan to attend medical school.

“I never intended to practice law,” he said. “But on the legal side, the freedom Bruce Sales was giving me to pursue whatever I wanted was a lot more exciting.”

While working on his dissertation, Suggs was asked to help with jury selection in the 1975 case of Erwin Charles Simants of Sutherland, NE. Simants had killed six members of a family and was initially found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. By the time of Suggs’ involvement, a second trial had been granted by the Nebraska Supreme Court due to improper contacts between the local sheriff, who was a key witness in the case, and the jurors. In addition to testifying for the prosecution, the sheriff had escorted the sequestered jurors to and from court and played cards with some of them. In the retrial, Suggs made detailed observations of perspective jurors, and Simants was found not guilty on account of insanity.

“In the first case, there had been so much focus on the psychiatric diagnoses, something the jury wasn’t familiar with,” he said. “We had to convince them that this man was insane without all the gloss of the psychiatric terms, which is what we did.”

While he agreed to help with the Chapman case, Suggs understood the gravity of defending an extremely unpopular figure. The work came with heightened precautions, and members of the defense received multiple death threats. Suggs’ firm hired an armed guard to be stationed outside of his office 24 hours a day and his mail was delivered to a designated room for pickup. Though they alerted the police of the more alarming letters, nothing ever came of the threats.

Suggs began his work on the case by organizing a demographic survey and interviewing Chapman’s friends and relatives in Atlanta. Meeting with Chapman himself presented issues, as he was being held in the hospital ward at Rikers Island. It would take half a day to get there and go through every level of security, Suggs said, and it was disconcerting meeting with someone he knew had committed murder.

“With him, and also with Simants, they looked normal at first glance,” he said. “But then you start talking with them, and it doesn’t take long to realize that something’s not right.”

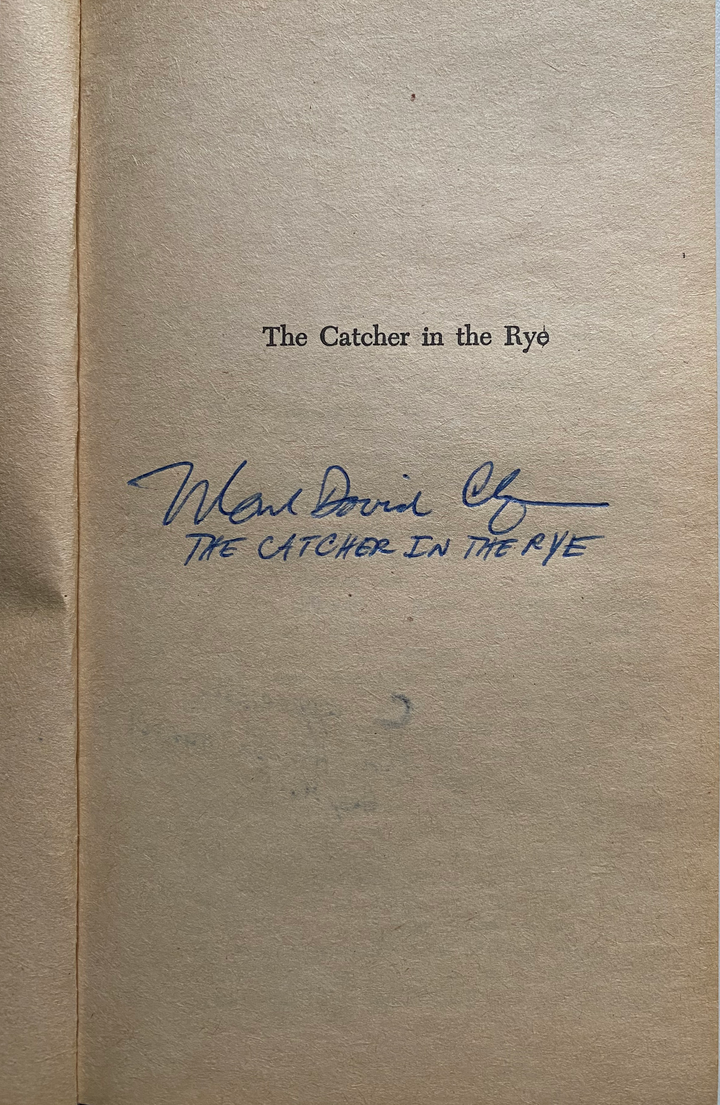

As he recalls, Chapman said his main motive for killing John Lennon was to increase the readership of his favorite novel – “Catcher in the Rye”. Unprompted, he had even given Suggs a copy he’d signed, promising it would be of great value one day.

In Suggs’ view, Chapman thought Lennon was a “phony”, a term the novel’s main character used to describe the people around him as inauthentic. When people would question this line of reasoning, Suggs said, it was because they assumed there was a rational reason for the murder when there was none to be found.

The psychiatric experts working on the case labeled Chapman as a paranoid schizophrenic with a narcissistic personality. In one of their meetings, Chapman told Suggs he was being possessed by two demons who were commanding him to kill the lead defense counsel.

“And I said, ’Has he said anything about me?’ and he said, ’No.’ I said, ’Well, if he ever starts talking about me, let me know.’ That was the last I saw him,” he said.

Chapman pleaded guilty prior to their final meeting, and there would therefore be no trial. Had one taken place, Suggs said, he would have wanted to use a similar approach to the Simants case by showing the jury in simple terms that Chapman was clinically insane.

“On one hand, I was truly convinced that he was insane, and I think he needed to be at a mental facility,” he said. “So I felt disappointment at that.”

On the other hand, Suggs said, it would have been a tough case to try. His wife was pregnant with their second child, and alongside the publicity and threats that came with the case, it would have taken up a great deal of his time.

In the years that followed, Suggs worked on many antitrust cases in New York and eventually relocated to the Midwest. He worked in mass tort product liability litigation, usually against large drug companies, started his own firm and later worked with two other firms in a national practice, retiring in 2016.

Chapman was sentenced to 20 years to life and remains in prison to this day.